Helicopter aerodynamics by Dr Colin MillPublication: W3MH issue 1In future issues of W3MH I will be concentrating on aspects of helicopter aerodynamics and I would

very much appreciate your suggestions for topics of interest. I guess that, unlike many of the

other contributors to this magazine, I am one of the back-room guys who is not too well known so

for this first issue and at the risk of boring you all I thought I would spend some time explaining

my background, how I got involved in model helicopters and what it is about them that fires my

interest. As for my background, I was until recently a lecturer in a university physics

department. My research interest was in atmospheric physics and teaching mainly electronics and

computing. I am now running my own design company, CSM, whose main product at the moment is the

Northern Helicopter Products (NHP) heli/aero simulator, so if you are looking for an unbiased view

of flight simulators don't ask me.

My interest in radio control dates back to the late '50's. I was about 5 years old when my father

built an R/C model boat (a Veron Marlin for those who remember them). This he fitted with ED valve

(thermionic) single channel gear modified to give a single proportional channel by variable

mark-space ratio modulation. The modulator was, believe it or not, mechanical! The mark/space ratio

may have hovered around 50/50 but the work/fail ratio of this gear was closer to 1/99. The

unreliability killed my father's interest in R/C but I was totally hooked. Given the performance

and reliability of early R/C gear I suspect anyone suggesting radio control for model helicopters

at this time would have been instantly locked up. For me the progress towards better R/C gear was

not that fast, being a mixture of home build and second-hand. My first R/C gear of about '65

vintage still used a valve at the transmitter end. Come to think of it, my first multi-channel set,

a 10 channel reed outfit, still used a valve in the transmitter output stage. I never rated the

reliability of these early R/C sets and confined it to boats while flying control-liners and

free-flight.

Involvement in models came to a halt during my undergraduate years but was revived when, as a post-

grad. student, I found myself working with Ian Stromberg, a keen R/C flier. I still have the slope

soarer (a Soarcerer) that I built then, complete with its home built Micron 27MHz radio. The servo

amplifiers in this were a work of art and used discrete transistors which you had to file down a

bit to get in the available space. Helicopters didn't even figure in my thinking at all until

around 1987 when by chance I read an article in Radio Control Models and Electronics on the cyclic

controls of helicopters. I had, up to that stage, what seems to be the typical fixed-wing fliers

attitude towards helicopters - they're expensive, all you can do with them is hover, they're as

interesting as watching paint dry, and I don't want anything to do with them. My attitude didn't

change over night but I did find myself reading the helicopter articles in the model magazines

rather than skipping them. The final spur to venture into helicopters came in 1991 when the

University turned down my promotion. I felt I really would have to work much harder - on my

hobbies! Within days I had an MFA Sport 500 collective, a set of Futaba Challenger Heli radio, a

stack of Model Helicopter World back issues, and some R/C helicopter books. Luckily, Ian Stromberg

decided to go along with my insanity and bought an identical set of gear so we could learn

together. The reading matter made us realise just what a challenge we had let ourselves in for. The

more we read the more daunting the flying seemed to be. The consensus seemed to be that it would

cost a fortune in broken bits before we could even hover.

A simulator seemed like a good idea. I had a 486 PC but, at the time, the only simulator available

in the UK was not available for the PC. Buying a simulator and a machine to run it on was outside

my budget (remember, I hadn't got the promotion!) In 1986 I had used a Sinclair QL to numerically

model propellers for optimising electric flight, but the speed at which this program ran

(walked?) made me wonder if there was a realistic chance of a proper numerical model of a

helicopter running in real time even on a 486. Some quick 'noddy' programs showed just how much

processors had progressed from the 68008 of the QL. It looked as if the sort of sums needed could

indeed be done with enough time left over for the graphics, and so the idea of writing my own model

helicopter simulator was born. Although I had a fair understanding of fixed wing aerodynamics, all

I knew of helicopters was what I could guess from the propeller theory used earlier. I got a copy

of Rotary-Wing Aerodynamics by Stepniewski and Keys (ISBN 0 486 64647 5) to bone up on the subject.

Now the interest became an obsession. The more I read the more fascinating the whole subject

became. A couple of months of frantic reading and programming followed and resulted in my first and

very user aggressive simulator. Definitely for private use only! I used this for about 40 hours

before daring to try the real thing. Having set up the helicopter on a test stand it took me one

fairly unproductive flying session to get used to the different feel of a real transmitter after

using the simulator with a couple of IBM joysticks, but on the second session I got the thing into

a reasonable tail-in hover and held it till the tank was almost out. I guess anyone who has learned

to fly a heli will know the sense of achievement at that moment. There are just so many manoeuvres

a heli can do that you can ke p on getting a buzz from doing something new with no

chance of ever running out of challenges.

Just in case you are thinking of trying R/C helicopters here are my list of tips for beginners,

though I bet

every W3MH contributor will give you a different one.

Resign yourself to the expense. If your starting with no existing gear at all you need £700 minimum

to get up and running. Crashes average £70 a time. Its cheaper to learn Indian club juggling with

(full) Champagne bottles.

Read all you can. I found 'Learning to fly Radio Control Helicopters' (ISBN 1-85486-025-9) and

'Setting up Radio Control Helicopters' (ISBN 0-85242-975-4) both by Dave Day to be very helpful.

Learn with a friend. Having someone at the same level as yourself to bounce ideas off is really

great. Experts can be very depressing.

Use a test stand. This allows you to set up the helicopter (especially the engine). You can't go

through life getting the model shop/ local expert to set up your heli every time you bend it so you

might as well start doing the job from the start. My test stand is a 'WorkMate' and some rope.

Get a training undercarriage. The usual 'crossed sticks' type (shown in photo fitted to my Sport

500) will allow you to get away with murder. Shorten sticks progressively to wean yourself off the

training gear - 'cold turkey' removal is too much of a shock.

Get a collective pitch helicopter. Although there cheaper, fixed-pitch machines are much harder to

fly than collective pitch ones. Some of the fixed-pitch machines are great fun but I have seen a

world-class flier have real difficulty doing a circuit with one.

Get a gyro. Although it is possible to fly without a tail rotor gyro, it is a lot harder. The

pioneers who learned to fly fixed pitch and gyroless have my full admiration.

Simulators. Now, given my financial interest, you wouldn't expect me to miss simulators off this

list. Just a few hours on a sim can save a lot of time on the flying field. If you can, borrow a

friend's. That way you get to drink their coffee and burn their electricity.

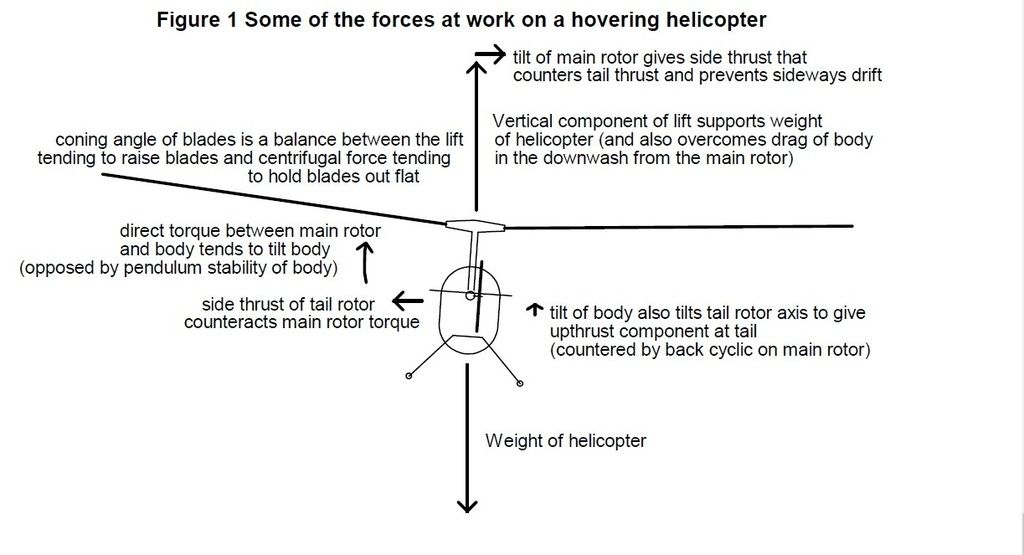

For me, improving my understanding of why helicopters behave the way they do is almost as important

as improving my flying. By way of a short introduction to heli dynamics for those who have never

given much thought to how helis fly, I have shown in Figure 1 just some of the forces acting on a

helicopter in the hover.

Next time I'll look at the way the main rotor generates lift and the power needed to drive it.

Similar topics (3)

Similar topics (3)